My Brother’s Keeper

My Brother’s Keeper is a follow-up story to Twoc’ing. Told from Charles Holdsworth’s point of view, it describes what happens a decade after the incidents shown in Twoc’ing. Unfortunately, it looks as if the two brothers are unlikely to be reconciled.

***

‘I put it to you your whole story is a tissue of lies!’

‘No! I don’t lie! Never!’

‘Really?’ the barrister paused and I couldn’t think of anything to say. Then, ‘No further questions,’ and the bastard sat down.

I don’t remember much else of Peter’s appeal against his conviction, other than we had to travel a long way from home. Dad drove and Mum sat in the back. George and I met the other two there, not knowing they’d changed their stories. They said, in court, we told them to say Peter was driving. Apparently, we ‘threatened’ them by saying they would be ‘ostracised’ at school. As if saying what would happen if they stepped out of line was a threat. Surely it was obvious you don’t annoy George or me if you want to be in our gang? It was a fact, that’s all. Dad reckoned those two boys decided to change their story as they’d already gone to comprehensives for their A-levels and re-joined the proletariat. Where they belonged.

The court believed them, not me and George. They said Peter’s conviction was unsafe and unsatisfactory. There was to be no retrial due to a ‘lack of public interest.’ Dad was furious with the barrister for tricking me, but they wouldn’t let Dad go to tell him off. Once he calmed down – we went to a pub for lunch – Dad decided he should have paid more attention to the idea they (the Army) didn’t like taking people who had criminal records. Dad said he had failed to appreciate how much taxpayers’ money they would waste getting their man cleared ‘by hook or by crook.’ At least the police back home let it be known they ‘weren’t looking for anyone else in the Peter Holdsworth case’ – George’s dad had a word with the Chief Constable when they met for their weekly round of golf. We got on with our lives, and Peter disappeared back into the army.

That was all a decade ago and Peter hasn’t been in touch. He’s never apologised for ruining all our lives. I mean, after that experience in court, how could I pursue a career in law? What if I ended up having to work with that barrister who chewed me over? Instead, we decided I should train in accountancy. Which has worked out well as I manage George’s accounts (he now runs the family estates). Also, it means Lucinda and I can live nearby. We visit Mum and Dad regularly.

Talking of Mum, she finds it difficult to say it’s Peter’s choice he’s stayed away – he doesn’t even send Christmas cards. Mum’s been officially depressed for a couple of years, and Dad’s cancer diagnosis hasn’t helped. Lucinda does what she can, but, with young Henry to look after and number two on the way, she does get a bit tired now and then. I find it easier to sleep in the guest wing these days. As we’ve all pointed out, I might be able to change a nappy (it is the twenty-first century, and I know my duty), but, as we’ve all said, given I have a full-time job, I can hardly be expected to get up in the early hours when Henry cries for his mummy, can I? Besides, by this stage, he really ought to be sleeping through.

That’s why I’ve had to track Peter down: Dad’s cancer. Dad’s quite cross thinking he might die without Peter making any effort to return home. The letter is burning a hole in my jacket pocket as we cross the parade ground. I glance at Peter, doing the quick march, taking the salutes. Taking, not giving, salutes. When I discovered where he was, who he was, I couldn’t believe it. He’d gone in as a criminal to be a private, junior soldier, and that sort of person doesn’t get to be a commissioned officer. But those three pips on his shoulder had to be real.

For want of something else to do, I looked around. I saw fit young men in singlets and shorts doing exercises: lovely flat stomachs, muscles and most of them knowing not to show any body hair. We got to the building where Peter had his office.

‘Sorry, sir, but I need a sign-off on this.’

I didn’t bother to see what ‘this’ was, and entered Peter’s office uninvited. A large enough space. It was neat, just like his bedroom used to be at home. Peter stood in the office doorway, scrawling his name. Sloppy. I always read everything before I sign it. The office window looked out onto those young men doing their exercises. I tore my eyes away – with Peter distracted, I ought to have a look around. The degree certificate on the wall wasn’t Oxbridge, nor Russell group. There was one photo on his desk, but that wasn’t family.

Peter finished whatever he was doing and came to sit behind his desk, gesturing at me to sit opposite him, the other side of the desk.

‘I see you’ve had a Joan Hunter-Dunn moment.’ I nodded towards the photo, which was of a girl in tennis whites. Raven-haired rather than fashionable blonde, and somewhat curvy for my taste, but she had smiled prettily enough for the camera shot. Peter glared at me. Betjeman is hardly a classical poet, but he was laureate for a while so his ‘Subaltern’s Love Song’ should be reasonably well-known.

‘For your information, it wasn’t Aldershot.’ Peter said, ‘But yes, that is a picture of my fiancée.’ When did you find time to know anything about poetry? I thought, your bog-standard degree certificate says engineering, not English Literature.

‘So, why are you here?’ Peter, direct as ever, went straight for my jugular.

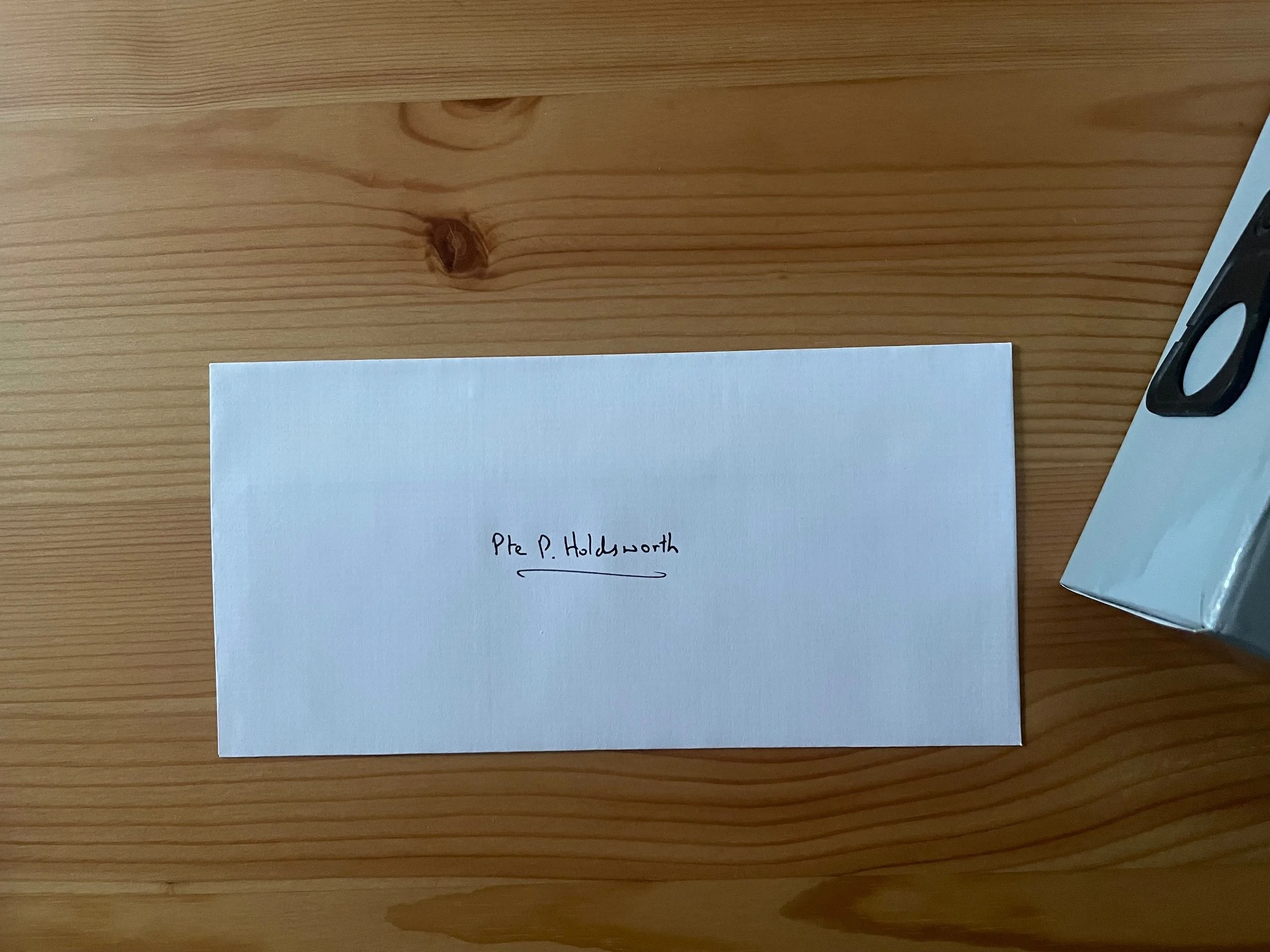

In reply, I reached into my jacket pocket, and tossed Dad’s letter onto the desk. It was superb. I could not have placed it better, the name on the envelope square in front of him. He could not possibly fail to read it, and he ought to recognise the handwriting.

He barely glanced at it. He wasn’t going to refuse to open it just because it said ‘Pte P Holdsworth,’ was he? Going to get precious because it got his rank wrong? Oh, well. Never mind. There was only a small chance my brother would have changed. Would have recognised his loyalty to us, his family. However, I had promised to try.

‘As you know, Dad’s got cancer –’ I began, but I was interrupted.

‘No, Charles, I don’t know that. No one saw fit to inform me. Like no one told me about your wedding. Nor did I get an invitation to your mum and dad’s Silver Anniversary. It has all passed me by.’

‘We put it on Facebook.’ For the moment, I decided to ignore the ‘your mum and dad’ comment.

‘You expect me to waste my time searching you out, following you on social media?’

‘Wake up, Peter! This is the twenty-first century! Everyone’s on social media!’

‘I am fully aware of social media, but families generally talk to each other.’ Peter had still not raised his voice. He was reminding me of Dad doing his pre-explosion, gritted teeth bit. However, I was not about to be put off by my brother.

‘And mum’s got depression – it’s about time you did your bit for them. Lucinda can’t do it all.’

‘Your mum’s got depression. My mother is dead.’ Now Peter had stunned me. What new lie was this? He continued: ‘And, before you say anything, I can show you the results of the DNA tests.’

At that moment, there was a knock on the door and coffee arrived. Not that the politeness mattered as, once the orderly left, I had to sit there, coffee getting cold, while Peter went through this fantastical tale about Dad getting this nineteen-year-old intern at his office drunk and pregnant because his wife – my mother – couldn’t have kids. According to Peter, Dad had ‘chosen well:’ the intern had no family. The intern left Dad’s firm at the end of her internship (nothing unusual in that) but, instead of going home, was holed up in a flat until she gave birth. The baby was taken away; she was kicked out with threats, amongst other things, that if she ever got in touch again, she’d be charged with harassment. Inevitably, she descended into sex work, drugs, illness. They found each other by chance. Peter had gone to their local hospital with a friend whose sister was in for a minor operation and the patient in the next bed, groggy with anaesthetic, mis-identified him as his father. After an initial, confused conversation, and a reluctance to believe, as things like this ‘don’t happen in real life,’ Peter agreed to the afore-mentioned DNA tests which confirmed their relationship. It was then easy to go in for the further tests for compatibility and possible bone marrow donation. The donation was given. There was brief recovery during which the two of them started to get to know each other. She took pride in his promotion. Then suffered a painful relapse and a long, slow death.

Peter stopped. Staring at me the whole time, he had delivered his spiel in a monotone. No inflection and no emotion. I looked out of the window onto the now empty parade ground. It was obvious to me his story was all lies. I was living proof Mum could get pregnant, so his opening premise had to be false. She got pregnant with me when Peter was a month old, so she must have been fertile. The pause was becoming a silence. It was even silent outside: where had all those nice young recruits gone?

‘Why on earth were you visiting someone else’s sister when you don’t visit us?’ I had to say something. Peter reached for his photo, turned it so I could see the image more clearly. ‘She was my friend’s sister,’ he said. Still not my type. I tried again: ‘She must have been disappointed when you deserted her for an old woman.’

‘My mother wasn’t old. And they became good friends.’ Oh, my God! I thought, we’re in fairy tale romance territory here. It was time to rain on Peter’s parade.

‘I’ve seen your birth certificate,’ I said. It was one of the many documents I had been shown. I was taking over once Dad was no longer able to run their lives – Mum was no good at that sort of thing. ‘Mum and Dad’s names are on it as your parents. You can’t change that. In law, they are your parents.’

‘I have the DNA evidence,’ Peter repeated, ‘Do you really think they’d go to court?’

I had an idea what he meant but, by mentioning the court, he’d made a mistake.

‘Court? You know all about court cases, don’t you? They never charged anyone else. They never looked for anyone else.’ I leant back in my chair, and waited.

‘I didn’t do it,’ he said, ominously calm – Dad would have exploded by now – ‘and you know I didn’t do it. I was not the driver of that car.’

I shrugged to show it was all irrelevant. ‘Are you really going to let a minor dispute from our childhood keep you from your father’s deathbed? He’s upset. He wants you there.’ I pointed at the letter. Peter ignored it.

‘If I turned up, what am I supposed to say?’

I stared. Was he so stupid? ‘Say “sorry,” of course. You’re the one who left. We’re still your family.’ I knew he was to apologise: Dad had made that explicit in what he wrote – he’d given me the envelope unsealed so I knew I had permission to read the contents.

‘No, Charley-boy,’ Peter said and I tensed. How dare he use that childhood nickname just because Dad wasn’t here to tell him off.

‘No, what?’ I replied.

‘I’m not saying sorry to anyone.’ He folded his arms, but showed no other signs of not being fully relaxed. It was as if he didn’t care whether I told Dad or not.

‘You’ll regret this,’ I said in an unconscious echo of our childhood squabbles. What Peter didn’t know was Dad was drawing up a new will. We’d already decided either Peter came into line, or I got the lot (Dad wouldn’t promise anything to Peter if he did come into line, but this was his only chance). ‘I’ve got everything right: career, marriage, kids. You have a criminal record, and nothing else.’ I got to my feet, ‘I’d advise you to read that letter and act on it appropriately.’

Again I waited, but he just looked up at me. I was about to remind him of his manners. I was the guest, I was standing, therefore –

‘How long before Lucinda gets fed up? Even if she was raised just to be wife and mother, I’m sure sooner or later, she’s going to rebel.’ Peter was using that calm, irritating tone that used to get me riled when I was a kid.

‘Why should she rebel?’ I faced him across the desk, his bland face reminding me of so many squabbles. How did he know Lucinda had taken to making sarcastic comments, wondering why I wasn’t at home more often? Dad’s put it down to her being pregnant again.

Peter steepled his hands, bringing fingertip to fingertip. ‘It can’t be easy for her. Being shacked up with a homosexual.’

‘I’m not gay.’ I fought the urge to shout it in his face, but that was what he wanted. He had that annoying half-smile, the one he’d deployed when we were boys on those rare occasions when we’d been left at home and he could say what he liked without Dad telling him off. I breathed in, forced myself to be calm. Not that there’s anything wrong with being gay. Of course there isn’t, but I was the one who was giving Mum and Dad the grandchildren they wanted. I put my hands behind my back, walked the two paces to look out of the window. A new bunch of squaddies had appeared. I carefully looked elsewhere. What would Dad say if I – I stopped the thought. There was that time a couple of the lads at school had called me ‘gay-boy,’ and Dad got to hear about it. He went mental, stormed into the Housemaster’s office, demanded, and got, those two dragged in there. They had to produce proof I was a homosexual, or produce written apologies by call-over the next morning. One for Dad, and one for me. We got our grovelling letters and nobody ever referred to the incident again. I made sure Lucinda was with me at every School Dance from then on. Problem solved.

There was a knock at the door. Peter called for the person to enter.

‘Everything all right?’ the new-comer, who looked like a cross between a vicar and a uniformed officer, poked his head round the door.

‘Come in, Padre. My brother’s just leaving.’

‘That’s good. Better not miss your appointment.’ the Padre said, walking into Peter’s office. The door swung closed behind him.

‘Appointment?’ I said, ‘but we haven’t finished.’

‘Oh, I think we have Charles, I think we have.’ Peter was standing, reaching for his cap.

‘You didn’t answer my question. What appointment is more important than what we have to discuss?’ The still unopened letter lay on the desk. Peter took a deep breath.

‘In the past, Charles, you were able to dominate me because Dad especially, but also Mum, your mum, condoned it. But the past, as they say, is a different country, where things were done differently.’

I closed my eyes in pain. He couldn’t even get the quote correct: The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there. Not that Peter was bothered, he was still jabbering on.

‘Yes, I have “issues,” Charles, and I’m dealing with them along with grief for my mother. The Padre has set me up with some counselling, and I don’t want to be late. I’ll get someone to show you out.’ Peter walked round his desk and held his office door open for me to leave first. The Padre stood aside, not commenting.

Before I knew it, I was being marched back to where I’d left my Audi A4. We skirted the parade ground. My escort watched me drive through the gates. The barrier dropped behind me with a clang. That clang noted the futility of my mission and the finality of its failure.

I set the satnav for home and smiled. Dad’s cancer was terminal. I was getting the money, and, when he’s dead, Lucinda can do what she likes. It’s not as if her brother is going to abandon me.