The “Nearly” Daughter-In-Law

This is my “seven objects” story from the workshop I led last October. The challenge was to write a short story having just seen the seven objects I presented to the group. Everyone was able to make a start in the time given, and the completed stories were presented to the group two months later.

Ernst Stavro Blofeld had his white Persian cat, Sir Harry Ford-Smythe had Chinese ‘Cloisonne Health Balls’ – an acquisition from when he’d been in Hong Kong. Every time Nikki had gone to see him, he’d be clanking them, rotating the two hard, hand-decorated bell-balls in his left hand, watching her from under hooded eyelids. She’d wait until, with a sigh, he replaced them in their little green box. All she could see was the cartoon villain playing Lord of the Manor; with his bald head, he even looked a bit like Donald Pleasence. James, Sir Harry’s son-and-heir, in the early days of their friendship, had made her watch all those outdated Bond films and she, at that time being grateful for the way Sir Harry and James had made her feel part of the family, had complied.

Perhaps that compliance made them assume she would fall in with the rest of their plans, but Parliament had just made same-sex marriage legal. Did it really matter if James didn’t give Sir Harry any grandchildren – sorry, grandsons? Of course not. There were plenty of organisations that could help them trace the next heir, if one was required. However, that was not how the Ford-Smythes saw the situation: Nikki, with her orphan status and her desirable waist-to-hip ratio (‘excellent for child-bearing’), was perfect for the part. Also, as if this was the clincher, the invitations had already been printed. Sir Harry gestured at the open box full of A5 cards ready to be addressed to the great and the good of the village, telling them his only surviving son was marrying Nichola Lauren White on Saturday, 21st June 2014, at St Giles’s church and afterwards at the Manor. It would be the Manor, the ancestral home, she would be marrying into. She was being offered the chance to be ‘chatelaine to hundreds, if not a thousand, years of history.’

The row erupted the previous evening in the studio when James arrived from London without warning. Her studio, part of the outbuildings to the Manor House, was converted from the eighteenth-century stable block, all mod-cons. Downstairs along with the studio, there was a large kitchen-diner and an equally large living space. Upstairs, there were three bedrooms, the master with an en-suite; as well as a family bathroom. The whole affair was a bit out of the way; Southampton being the nearest mainline station and then an hour to London.

Nikki had thought she’d made it clear her studio, and her home, were sacrosanct. James said different: as her landlords, they could come and go as they pleased, and he was here to tell her they were expected at the Manor House next morning for coffee and congratulations. Just the three of them. The main party was next week. It had taken her half a minute, less, to find the images and show him what she, and the whole online, Facebook world, knew: another young man from the newest gay bar.

‘Of course, he’s not a boyfriend, darling! Just a quickie and we went our own ways. I mean, I can hardly bring him home to the village, can I? And, before you start bleating about it being the twenty-first century.’ Nikki’s mouth was open to say that, or something similar, but James carried on: ‘I have to produce an heir of my own. And, ideally, a spare. All very boring, all very traditional. But there it is.’ It was all about the baronetcy, the hereditary title had to stay in the family.

In other words, she was the suitable fiancé he could take home to produce the next Sir John/Jack/Tommy - whoever. He had taken Nikki home as, she thought, a fellow artiste. She’d played the Steinway, and the old man was charmed. As James put it, as his wife, all she had to do was look pretty, convince Daddy she could run the home for him, and allow her purported husband (who hadn’t even ‘popped the question’) to run around making a name for his gallery. He even repeated his offer to showcase Nikki’s ceramics – which was more than such work-a-day material deserved, but oh well.

On hearing that, Nikki had grabbed the nearest pot and flung it against the wall. Which had earned her a ‘Temper! Temper!’ from James. Nikki’s argument was she’d taken the lease on the Old Stables, complete with studio, in good faith; its cheapness being put down to its position in the countryside. James laughed. Surely, she’d realised? She must have – oh, dear, how could she have been so naïve? A home-grown wedding using the Great Hall and the grounds was excellent publicity for both father and son. There’d even been interest from the women’s glossy magazines. Oh, God! Was James going to have to go through with it by being yoked together with some girl from eastern Europe or, heaven forbid, East Asia? It wasn’t as if Nikki had come from anywhere – her family, such as it was, had hardly made anything of themselves, had they? There was no-one to be offended, was there?

Nikki’s mum had been a single parent, who’d been used and dumped three times. Mum didn’t learn. Even if there were no more kids, lots of ‘uncles’ came through. Only Uncle Bob, with his tales of all the places he’d been in his lorry, lasted any length of time. Then, one day, he didn’t come back; and mum carried on working as a cleaner, or shop assistant, or dinner lady, just to keep their heads above water. For the children, Saturday and/or evening jobs became compulsory. Her brother, bullied for his skin colour until he put weight on at puberty and discovered his fists, joined the Army at the first opportunity, and disowned them. Her younger sister, Amy: peaches-and-cream complexion, pretty, blonde, early developer, fell into the clutches of an older ‘boyfriend,’ until she over-dosed at twelve, and was taken into care. Nikki and Mum were banned from visiting.

Looking back, Nikki realised she’d been lucky. Miss Mountford, her Music teacher, had taken her under her ample wing, guided her through her grade eight piano and the obligatory GCSEs, and pushed her into doing Art and Music at the Sixth Form Centre. It was only after Nikki got to university, she found out Miss Mountford had even paid for her Music exams. It was in her final year, still trying to cope with Mum’s passing, she met James. Had she been flattered at James’s attention and praise? Yes, she had. When she’d been invited to dinner at his dad’s Manor House, had the old man’s gallantry, his praise of her musical expertise as she played their piano for them, been equally pleasing? Of course – especially when he helped get her more private pupils and even pushed her to take on the part-time teaching job (music and art) at the local village primary school.

As a quid pro quo, she’d been happy to accompany James to local events as his ‘plus one.’ It was a relief in many ways not to have to negotiate the general pawing and how-far-are-we-going scenario after every date. She’d had enough of that at university, culminating in Damien Fortescue demanding full sex after he’d bought her one drink at the student bar – the beer went all over his face. A pity when it landed on his forehead, it was still in the glass. Damien involved the University authorities and the row split her year group: the girls on her side, the lads either keeping their heads down or mutely siding with Damien and his cronies. But she’d been the one who had to apologise ‘for not being able to take a joke,’ or face expulsion.

As a ‘frigid, ball-breaking lesbian,’ she’d been left alone after that. Not that the last word was true. Despite herself, despite her mum’s experience, despite her younger sister’s ‘life choices’ – Amy was now a ‘model,’ but Nikki had never seen any photos – Nikki still found herself attracted to boys, rather than girls. Their degrees finished, she and James moved to London, she fired with hopes of landing a place with a prestigious orchestra, and he equally determined to have his own gallery. Lacking the connections, Nikki didn’t even get a foot in the door. All she could get was supermarket work and a few private lessons for those kids with parents who still thought some skill on a piano helped their offspring to rise up the social ladder. She only did the pottery class to get her out of the damp, cold flat on a winter’s evening.

James was the tutor, which was why she got the class for free. Not feeling threatened by him, she blossomed under his instruction and was absurdly pleased when he took one of her pieces for his gallery. She had not thought her ‘bird on a branch’ was worth much, but it sold and there was a demand for more. A second career, James had called it, and suggested she find herself an out-of-town studio. What he had not said was his father was making assumptions about the two of them as she would be living on the family land (‘Came over with the Conqueror, you know!’). Sir Harry had paid for the conversion of the old stables. Nikki had moved in. James visited on an ad hoc basis, when he wasn’t busy in London.

Her supposed fiancé was conspicuous by his absence: ‘You’re the one refusing to get married! Not me, darling! I’m all for it.’ Nikki had made her feelings clear, and shown the evidence to the older man.

Sir Harry sat back in his chair. Nikki returned her phone to her V&A tote bag, one of the few remaining tokens from her time in London. She was due to give another piano lesson soon to a new pupil, and George’s music nestled in there, awaiting his uncertain fingers.

‘The piano,’ Sir Harry said. Nikki looked at him. He wasn’t expecting her to play, was he? He carried on: ‘The photo, on top of it. Can you get it, please?’

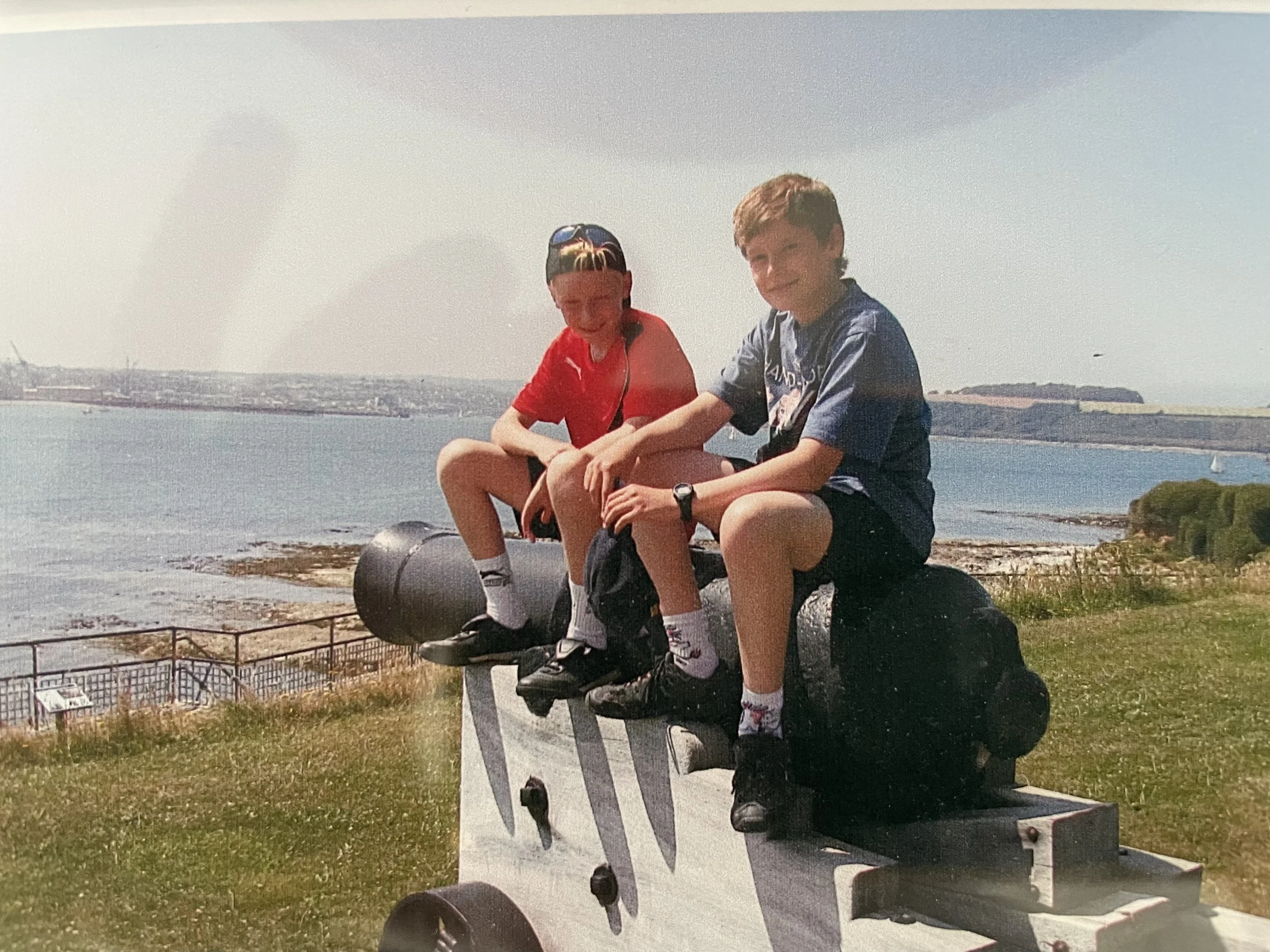

She’d seen it before, a small, framed (fifteen centimetres by twelve) image, but given neither father nor son ever mentioned it, Nikki had not felt confident enough to ask questions. The photograph of two young boys sitting on a cannon and smiling into the camera appeared out of place. She did as she was asked. Sir Harry held his hand out so, a little puzzled, she gave it to him.

‘That’s Harry,’ a shaking finger pointed at the larger boy, ‘Such a little charmer. And that,’ the finger moved a couple of centimetres, ‘is his little brother: James.’

Sir Harry gave her back the image. Nikki took it, looking at it as if for the first time. As she gazed, she learned the boys were on holiday with their mum. They were in Cornwall. The photo was taken just outside Pendennis Castle, but Sir Harry didn’t know if they were supposed to be climbing the cannon or whether their mother let them do it: ‘She wasn’t so good at following the rules. Perhaps that’s why young Harry was in the front passenger seat as they drove back. You see, I wasn’t there. She’d taken the boys to see their grandparents – family place down in Cornwall, you see.’

They told Sir Harry it was quick. ‘They said “instantaneous.” But it can’t have been that. Even if it was for a split second, they must have seen the lorry, must have known.’ Sir Harry didn’t meet Nikki’s gaze. She re-examined the photo. She guessed it must be twenty years since it had been taken. Standing in awkward silence, she watched the Lord of the Manor struggle with his tears, but refusing to let them fall. There were no photos of the nameless wife that she’d seen, and only this one of the long-dead son. Before she could wonder further, she realised Sir Harry was still speaking.

She learned James had been thrown clear: a few cuts and bruises. Because, as far as the family was concerned, a newly-single father was not the sort to be able to cope with an eight-year-old, demanding child, James had been taken in by his aunt and uncle. Between them and his grandparents, he had been raised and educated. Sir Harry now wondered if it had been the right thing, but what did he know about raising children? But, given how James had turned out, maybe he should have ‘been around more.’

A newly-single mother would just have to cope, Nikki thought, and deal with the emotions of her surviving son. However, saying that wouldn’t help. If the father had wanted a normal son – not an emotional retard, whatever his sexuality – then they both should have been in front of the counsellors, if not the psychiatrists. She put the photo back in its place on the piano.

‘I’m not entirely stupid, Nikki.’ Sir Harry attempted normality, ‘I’ve known for years about his – what we used to call “proclivities” – but let’s just say I hoped. And then you came along and he moved you into the stable block. What can I say?’

Nikki whipped round, furious: ‘What you can say, Sir Harry, is “sorry” to your son for not being there when he needed you!’

‘But … but he had everything he needed! I had my businesses, and the running of this place. He knew where I was – I was looking after his inheritance!’

Her anger died, replaced by tiredness and the knowledge she could do nothing for either man. Nikki picked up her bag, if she stayed much longer, she’d be late for George’s lesson.

She had reached the door before Sir Harry spoke again: ‘You’d better go out via the kitchen. Mrs Scott left a cake – for the engagement. You, oh, you take it away. The doctor seems to think I ought to cut back on the sweet stuff. Mrs Scott said something about the cake tin being appropriate.’ Mrs Scott was the housekeeper-cum-cook.

Nikki did as she was told. The tin, if you can call a plastic container a tin, was sitting in pride of place by the tray of elevenses. There were even crustless cucumber sandwiches along with the coffee. She peeked a look: nothing wrong with Mrs Scott’s sponge, but did she really have to leave it inside a ‘Celebrations’ tub, given there was nothing to celebrate?

‘Section 21,’ James’s appearance in the kitchen, startled her.

‘What?’

‘Section 21. The landlord does not need to give any explanation for the tenant’s removal from the property.’

‘I signed a year-long lease.’

‘So what? We can get the lawyers involved if you like. Can you afford that?’

Nikki found she still had her hands on the Celebrations tub. She struggled: the temptation to fling the cake at him, whether still in its tub or not, was so strong. She breathed deep, straightened, and turned to the man who, until recently, she had thought of as a friend.

‘You do that. You kick me out. And in return, I will spread those images – which are still on my phone, James – far and wide across the village, among your father’s friends and business colleagues. I will start saying things about you. About how you forced me to take part in your plans – all of it!’

‘That’s not true. I never forced you to do anything!’

‘Who will they believe, James? I have the evidence.’

She turned back to the kitchen table, picked up the tub with its cake, and made for the kitchen door. She had time to get to George’s lesson, just. Maybe he’d cheer up if she bribed him with a piece of sticky, gooey, cake.

‘You’ll never get your pottery in any other gallery! And you can clear all those little, nondescript, birds and plant holders out of mine!’

‘Oh, dear! I was only giving them to you out of loyalty. Had two – no, three – offers in the last month. What’s a bit of commission between friends?’

James shrugged. She didn’t know, and at that moment, cared less, whether he believed her. However, his next comment stopped her.

‘I found Amy. She was in the same bar.’ James was holding out his own phone. Despite herself, Nikki approached to peer: the image was sharp, but the subject’s eyes were dulled. Nikki suppressed the flash of recognition.

‘There are a lot of blondes in London.’

‘It won’t wash, darling. That’s your sister, and the drugs are what all her sort do. Keeps reality at bay.’

‘How do you know?’ Nikki was suspicious.

‘Pillow talk, sweetheart, pillow talk.’

‘Your boyfriend’s her pimp!’

‘Oh, darling! Give me a little credit – he’s a gay policeman! They’ve been checking the joint for weeks!’

‘How come they haven’t worked out who he is – what he is, then?’ A thought: ‘But they will once I get these published! It’s not Amy.’

For a second time, she headed to the door. She opened it: ‘If that’s Amy, darling,’ the sarcasm dripped from her, ‘then you bring her here, to my home. Or you know what’ll happen.’

Like the other offers for her ceramics, she was bluffing. If there was any chance of getting hold of Amy and extracting her from her mess, she’d take what came her way. But that was a conversation for another day. She had a piano lesson to give. She made her exit, leaving James standing in the kitchen looking at his phone. What she did not see, so could not question, was the smirk on his face.